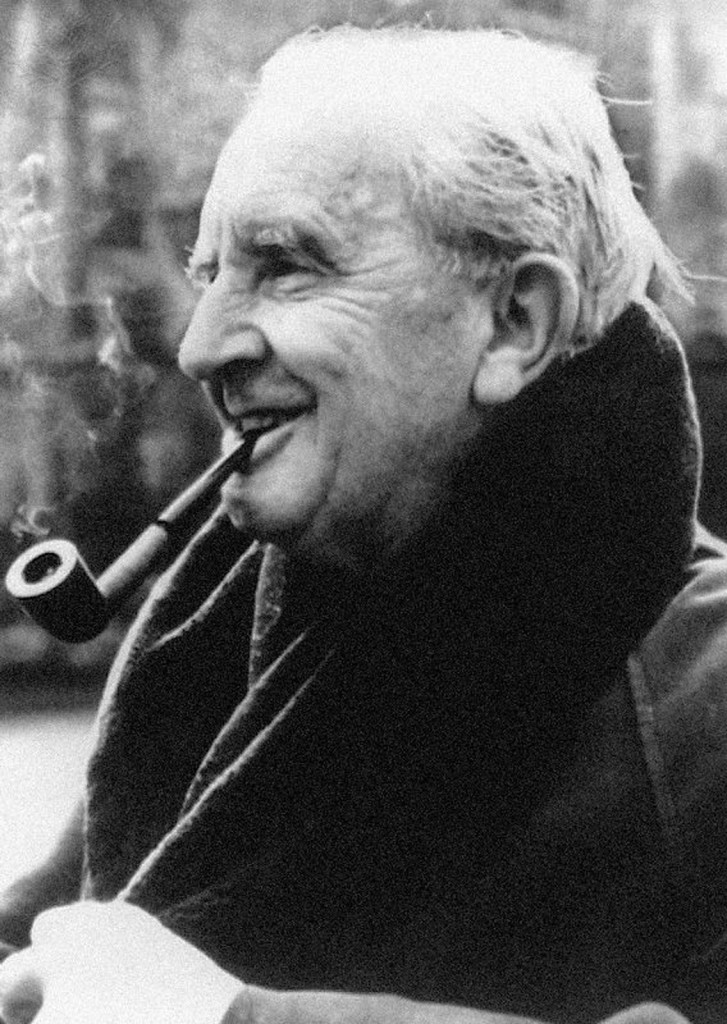

Lately, many of my friends are into HBO’s Game of Thrones and the History-channel-hit-turned-Comic-Con-favorite, Vikings. Perhaps—hot on the heels of Peter Jackson’s Oscar-winning adaptation of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy—these shows resonate with America’s growing fascination with the degeneration of urban, capitalist culture, and the prospect of a retreat to primitive societies filled with visceral, earthy, and noble people. I have been wondering why these types of stories attract us, and what will come of it. Naturally, my mind turns to the founder of it all, Tolkien himself.

It is no secret that Tolkien was vastly indebted to ancient mythology and to the great stories of the Middle Ages. Those familiar with his works and with old stories like “Beowulf,” “The Saga of the Volsungs,” “The Song of Roland,” “The Odyssey,” etc. will notice that several narrative details from Tolkien’s works were taken unabashedly from these much older tales. To mention a few examples: Boromir sounded his war horn in distress like Roland; both the dragon from “The Hobbit,” Smaug, and the dragon from “Beowulf” were awoken by thieves who stole cups from their treasure hoards; Túrin of “The Silmarillion” killed the dragon Glaurung by similar means as the Viking hero Sigurd killed the dragon Fafnir; and Middle Earth is full of magic rings like the one owned by Gyges in Herodotus’ “Histories.” Indeed, enumerating all of Tolkien’s borrowings from literary traditions of the past would take a lot of time, so I will leave this enormous task to the scholars.

I would like, however, to draw attentions to Tolkien’s far more fundamental inheritance from the Viking myths, which lies beneath many of the specific borrowings referenced above. Almost everywhere in Tolkien’s writings is a deep sense of both the memory and fear of loss. Death, which is but one form of loss, lingers everywhere, claims all, and defines much of life as long as the world lasts. The Shire becomes a rare haven untouched by the constant pang of loss, which pervades those times and places under the shadow of Morgoth and his servant Sauron. Tolkien had every reason to feel this loss very deeply. Tolkien was one of the few young men who survived the front lines of World War I, and he carried with him the horrors of modern warfare.

The existential bleakness of Viking mythology seems to have settled deep in his mind during his

studies of Anglo-Saxon and Old Northern literature at Oxford after the Great War.

Certainly, no other world than that portrayed in the “The Saga of the Volsungs” (a thirteenth century telling of a much older Viking saga) is so driven by fate, and so overshadowed by mortality. Life in the ancient North seemed but a hastening to death, and even the most valiant actions of the strongest heroes constituted but a prelude to an inevitable end. Even great men and women, who slew dragons and were faithful to their own, could but succumb to arbitrary fate when it sought them. Yes, there was some hope for those who died valiantly to through great deeds join the company of those heroes who have gone before. Both Sigmund and Tolkien’s King Theoden had this hope. The latter, as he lay dying, profoundly remarked, “My body is broken. I go to my fathers. And even in their mighty company I shall not now be ashamed.” Even still, death was ultimately marked by uncertainty.

Whatever comfort could be found in companionship was overshadowed by the fact that all reality was pregnant with separation. In the end, those with whom one’s “thoughts laughed” would be consumed by all-consuming fate, and, “soon it shall be that sickness or the sword rob thee of might, or fire’s embrace, or water’s wave, or bite of blade, or flight of spear, or dreadful age; or the flashing of thine eyes shall fail and fade; very soon ‘twill come that thee…shall death lay low.” Life ends, and, on the existential plane, little else can be known but that, “man appears on earth for a little while; but of what went before this life or of what follows, we know nothing.”

What Tolkien had that these Northmen did not was a sense of knowing the end—the “eucatastrophe”—that would redeem the heroes of old from the existential night into which they sailed after death. Tolkien believed that death and loss were laid in their graves by Christ through his passion and resurrection. Indeed, in “The Children of Hurin,” Turin’s grief-driven suicide is not the end of the tale; he comes back, along with all of the great heroes at the end of all things, and finally defeats Morgoth, who had endlessly tortured his family. The despair, or at best, ambivalence, that marks “The Saga of the Volsungs” is precisely what Tolkien believed Christ overcame. The tragic arbitrariness that marks the Old Northern myths, the resignation to that fate which claims even and especially those resilient ones, against whom, “iron was of no avail,” in life, is suddenly stripped of its finality. Thus, perhaps the most compelling thing about Tolkien is that though he was overcome by the universality and timelessness of loss, he refused ultimate ambivalence and despair. He believed loss itself would be lost in a time yet to come, and thus hoped on the precipice of his own death, along with Aragorn: “In sorrow we must go, but not in despair. Behold! We are not bound for ever to the circles of the world, and beyond them is more than memory.”

I am still unsure what about Vikings and Game of Thrones is so captivating to millennials. Perhaps the somber and vibrant Christological vision that we discover in the books that inspired both of the above ought to replace meandering demographic speculations with a resonant, even eternal, hope that there are no mere stories. You and I are separated from the white shores of the undying lands not by that walled gate through which we pass from childhood to maturity, but only by our own cynicism and our refusal to imagine that loss itself might soon be swallowed by resurrection.