Perhaps no other culture war in the past five years has turned so messy and long-lasting as the debate over book censorship in schools. According to the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom, in 2023 4,240 unique book titles were targeted for censorship, as well as 1,247 demands to censor library books, materials, and resources.

Originally centered on school curriculum and libraries, those trying to ban books expanded focus in 2023 to public libraries in general. PEN America found the number of titles targeted for censorship at public libraries increased by 92% over the previous year. They also found that book bans continue to be on the rise, as school libraries saw an 11% increase in 2023 over 2022 numbers.

What exactly is a book ban? PEN America defines a school book ban as “any action taken against a book based on its content and as a result of parent or community challenges, administrative decisions, or in response to direct or threatened action by lawmakers or other governmental officials, that leads to a previously accessible book being either completely removed from availability to students, or where access to a book is restricted or diminished.”

It appears that book bans don’t need to go all the way through to leave an impact on what students are reading in schools. PEN America found that 52% of the book ban cases between July-December 2022 were only “pending review.” Yet, when parents or administrators challenge the books, they are immediately pulled from classrooms or libraries until a decision is made.

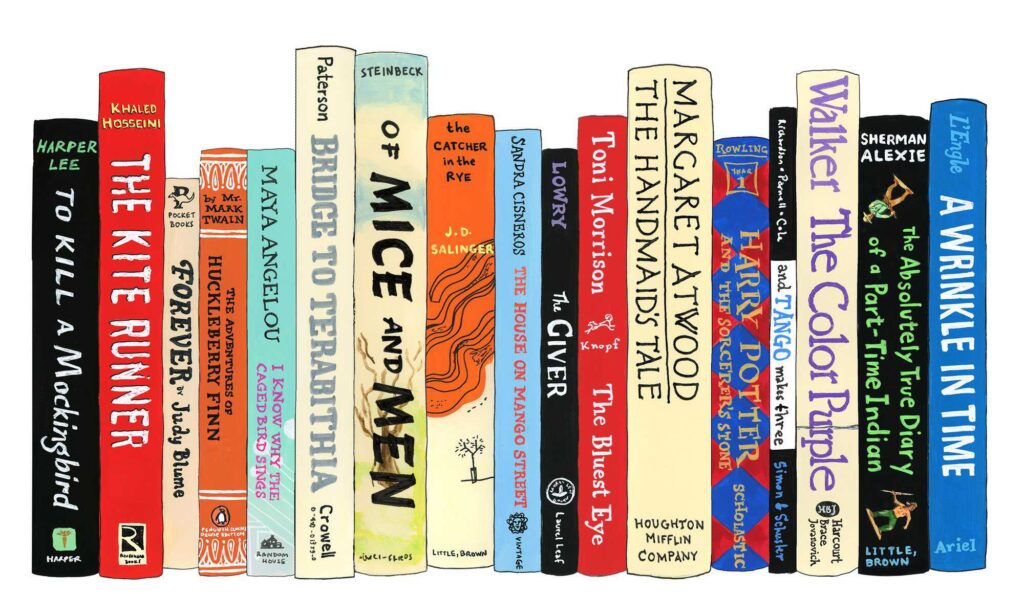

What kinds of content are in the books being banned? PEN analyzed 824 unique titles which were banned in 2022, and tracked them for themes. Of the 824, 44% include themes or instances of violence & physical abuse; 38% cover topics on mental health, bullying, substance abuse, and other health concerns; 30% are books that include instances or themes of grief and death; 30% include characters of color or discuss race and racism; 26% present LGBTQ+ characters or themes; 24% detail sexual experiences between characters; and 17% of books mention teen pregnancy, abortion or sexual assault.

Opponents of book bans say they are undemocratic, and Columbia compares them to similar book bans done by Nazis leading up to the Holocaust, in which book burnings were done on books written by Jews and leftists. They argue that wrestling with heavy topics is essential at a developmental age. Exposure to topics that may be uncomfortable or foreign for children can allow them to see other worldviews and develop empathy for people who are different from them. Books with BIPOC or LGBTQ+ characters can provide a child who identifies in this way with characters who identify with them. These opponents say that it is imperative for children with LGBTQ+ identities and/or children of color to see themselves represented in literature from a young age.

Proponents of book bans, on the other hand, argue that certain books contain sexual or controversial content that is not appropriate for children. In an opinion piece for the Dordt University school newspaper, one student made the argument that not all literature is equal. Books that openly discuss sexual acts are not for schools to hold–that job should be left to parents. New York Times finds that the advocacy group No Left Turn in Education seeks to ban lists of books it says are “used to spread radical and racist ideologies to students.”

How are Eastern students reacting to this particular culture war? Sydney Shine is an elementary education major and an aspiring educator who says that book bans in her home county of Bucks County started to take effect after she graduated high school. The books banned were not in the curriculum but rather in the school library. “When I was there, there was a club for LGBTQ+ kids, and I think banning books would be really harmful [for them]… they weren’t trying to force anything on anybody,” Shine said. As a future educator, Shine grapples with how censorship may impact what she can teach and the diversity of the students who may be in her classroom. “My future students might identify with that community [the LGBTQ+ community]. Those books should be books that are accessible to them,” Shine continued. While she said that censorship was harmful to students, it also impacts educators. “It can cause an obstacle to teachers for inclusivity,” Shine said. She encourages everyone to attend school board meetings and vote to “Make sure people in positions of power are people who will take care of the future of our nation–the students,” Shine concluded.

Meanwhile, Abby Kitchen, an English literature major, refrained from making any sweeping generalizations. As a literature student, she believes that “Literature is a necessary part to education.” What counts for literature versus what is a pleasure read with no real academic value is an important distinction, however. Kitchen criticized the vagueness of some legislation on book bans, which often ban anything involving “pornographic content.” Classics like “1984 and The Color Purple have sex scenes in them, but there is purpose behind that content in the book and there is meaning behind them,” Kitchen said. She separated these kinds of books from cheesy romance novels with no substantial purpose for the potentially offensive content. “Surely there are things you can take and learn from that book, but it’s not going to be anything huge and substantial,” Kitchen said. Would sweeping bans against sexual content include these classics? Where is the line? These important questions must be asked of legislators. Kitchen also pointed out, however, the complications of keeping books with sensitive topics in high school libraries. “A 14 year old freshman is so much different [from] an 18 year old senior… Especially in public schools where there are so many kids coming into one place and parents with so many different backgrounds and different ideas,” Kitchen said. How to keep every party happy is, indeed, a challenge public schools have been facing in recent years. In the end, Kitchen alleged that the responsibility for heavy topics should not fall solely on either parents or a single book. It is going to take more than either a book ban or one book with a different viewpoint to tackle some of the biggest social problems facing our society today.

The culture war over book bans point to a larger debate over the censorship of art. Do books, as an artistic medium, deserve protection from censorship on the basis of creative expression? Or, do legislators have a responsibility to protect children from what some see as potentially dangerous ideas before they are equipped to deal with them? It is a question the world continues to wrestle with.

Sources: ALA, PEN America, Dordt, New York Times