One of life’s greatest blessings and many frustrations is the wealth of incredible thought and philosophy that we have inherited. This leads to the sad reality that many of our most brilliant thinkers and philosophers lie buried underneath the tangled ivy of the sheer bulk of history’s literary work. Unfortunately, this is especially true regarding many of the brilliant female minds of the Middle Ages. And yet, it doesn’t have to be. My intention today is to offer to you an underrated, thinker, composer, doctor, visionary and Christian whom you likely haven’t heard of, but whose work is worth the investment to enjoy.

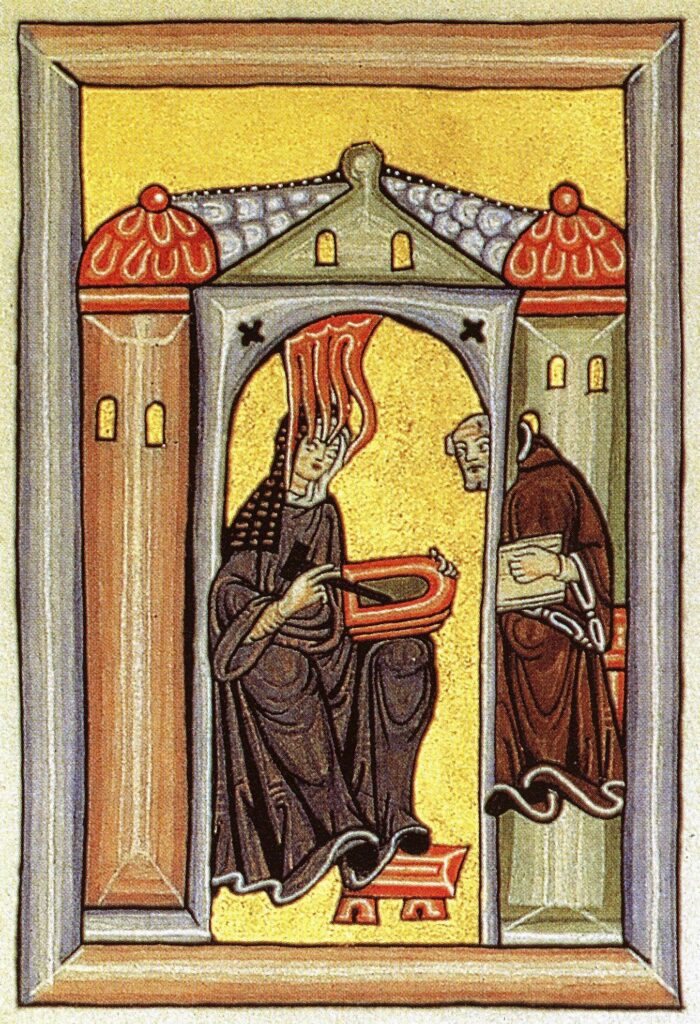

If you’ve ever heard of this 12th-century German nun, it was likely within the context of her impressive musical composition repertoire. St. Hildegard von Bingen’s extensive composition of Medieval plainchant and other liturgical hymns won her much respect in the historical music world. She’s also credited with having written the first morality play, the musical Ordo Virtutem.

While St. Hildegard’s many musical accomplishments are rightfully astounding, far fewer people seem to recognize the plenitude of her other intellectual endeavors. St. Hildegard belonged to the Benedictine monastic order, an order which highly emphasized the contemplative life and development of the mind. Through the mentorship of her fellow resident at the monastery, Jutta, St. Hildegard learned to read and write. Even from her early writings, we can see her deep roots in the already rich intellectual tradition she had access to through monasticism. Her literary repertoire extends across genres and themes, containing apocalyptic, visionary masterpieces such as the Scivias, treatments of virtue and vice such as Liber Vitae Meritorium, theological commentary on portions of the Bible in Liber Divinorum Operum and scientific, medical treatises like Causae et Curae. She’s also referenced as having gracefully stepped into political issues by writing eloquent letters to the different parties involved.

St. Hildegard’s work also extended past the intellectual, as she recognized the deep importance of physical life. She worked as a nurse for years within her convent, and her experience in the medical field both greatly influenced her community and writings. Even just reading her more visionary works, such as Scivias, I’ve been struck by how she conveys the unity of a person, and the importance of the relationship between the body and soul. One example of this is when she uses the analogy of an arm and fingers, with all their veins and marrow, to describe the relationship between the will and the intellect. While this might seem a rather weak example of her medical work’s impact on her visionary life, this is only one of many instances where she uses her understanding of the body to convey spiritual concepts. And, the fact that she uses the body as her metaphor for the soul in the first place is rather unique within her historical and philosophical context.

From her first biography on, Hildegard was considered a saint, and remains a saint in both the Church of England and the Roman Catholic Church. However, it wasn’t until 2012 that she was officially canonized by the Roman Catholic church. In 2019, she was proclaimed a Doctor of the Church, a title only held by three other women.

All in all, St. Hildegard’s work is expansive, covering the musical, medical, political, ethical and theological. Her ability to write winsomely and eloquently on so many topics, particularly at a time when basic education was not as widely proffered as it is now, is particularly remarkable. Based on the bit of St. Hildegard’s background that I’ve provided you with, you can probably agree with me at this point that she was a very accomplished woman. However, I’ve yet to explain why we, common folk, ought to appreciate her work. After all, what sort of impact can a nun’s almost a thousand-year-old writings have on our lives? Since her choral pieces are so representative of the excellence of her work, why should we seek out any of her other work?

One of my professors, Dr. Moser, lent me his copy of St. Hildegard’s Scivias at the beginning of the semester. While this reading is slow going at times, I can assure you that it’s worth it to give a chance to St. Hildegard’s more dense writings simply based on the beauty of her language and writing–and much more because of the intellectual and spiritual richness of her work.

St. Hildegard ought to be thought of more highly and widely than a passing mention distantly associated with music. While her writings are not the most widely known, they are highly representative of the beautiful work of many Christian female Mystics who were influential in their communities through their physical, spiritual and intellectual presences. From women like this, but especially St. Hildegard, we learn not just spiritual truths, not just new ways to marvel at the wonders of this world and of faith, but also much about life dedicated to pursuing the true, good, and beautiful. We learn that the intellectual life does not need to be divorced from a deep understanding and appreciation of the physical life. We become more fully human as we witness the picture of the fullness of creation and humanity that particularly St. Hildegard presents. So, I invite you to join me in brushing off the ivy that covers St. Hildegard’s work, and recovering the thoughts of this brilliant woman, so that we might weave her wisdom into our lives and witness the world anew as a result.