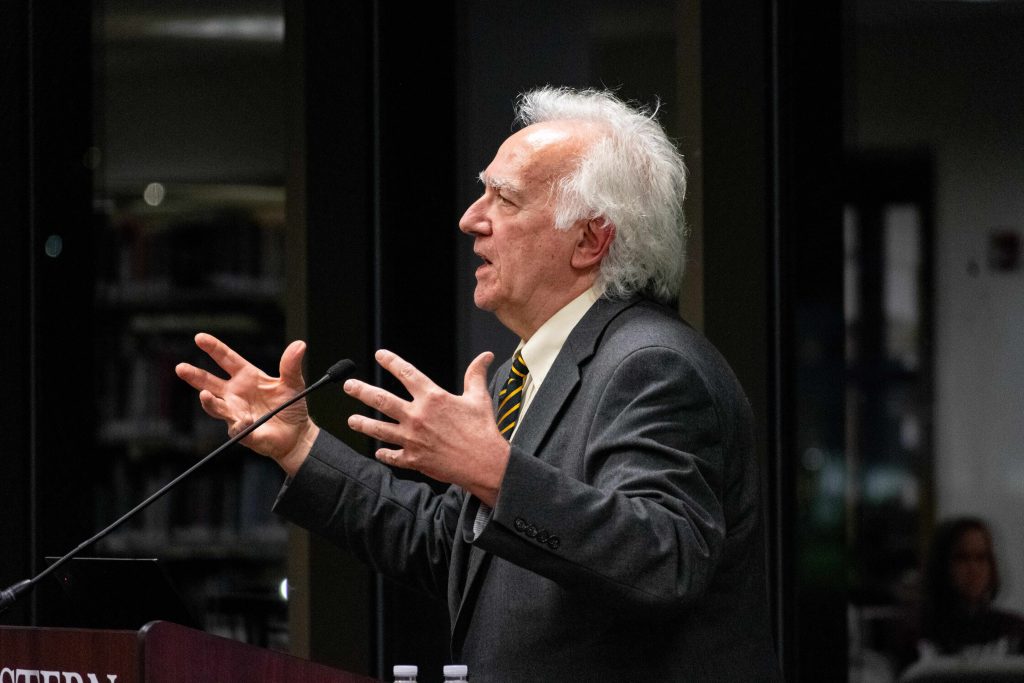

This past March, Eastern University had the pleasure of hosting famous historian Carlos Eire on campus for a series of lectures. Eire is a graduate of and professor at Yale University, specializing “in the social, intellectual, religious, and cultural history of late medieval and early modern Europe, with a focus on both the Protestant and Catholic Reformations” according to his bio on Yale’s website. He has been awarded for his famous memoir “Waiting for Snow in Havana,” which details his experience as a survivor of the Cuban revolution.

However, despite this impressive background, Eire came to Eastern for an entirely different discussion, surrounding his interest in the supernatural and its presence in Christianity and history. His internal dialogue on the matter has become public after the 2023 release of his book “They Flew: A History of the Impossible,” which explores the tension between modern scientific thinking and the historical accounts of seemingly impossible events. I had the incredible opportunity to sit down with Eire and ask him about his journey on this matter, exploring the boundaries of both Christian and historical thought.

Eire shared that the idea for “They Flew” started 40 years ago when he was visiting St. Teresa’s convent in Avila. He described the rather “mundane” tour; here was the kitchen, here was where everyone ate, here was the staircase, and here was the room where St. Teresa and St. John of the Cross levitated together for the first time.

Eire paused, and after a few seconds he verbalized the question I was about to ask: “Excuse me, can you say that again?” Certainly; this was the room where St. Teresa and St. John of the Cross levitated together. Eire explained that the way it was presented as a fact so simply kept him thinking about how in all religions, particularly Christianity, people grapple with the intersection of the physical and spiritual realms.

“I thought, ‘What’s happening here? Did that really happen?’ These were questions I was trained not to ask, much less answer. Those questions have always driven me in my work, but in this one [“They Flew”] especially,” Eire said.

Eire kept that interest in the back of his mind for a while, focusing instead on other projects and writings that kept coming up. He would occasionally circle back to the topic in a lecture or article, and once the pandemic hit, he found himself with a lot of time to start writing.

“When you think about the question of if they flew, does it feel like there’s a war between you as a Christian and you as a historian?” I had asked.

“No, it’s not a war. It’s not a conflict at all,” Eire said.

Eire shared that his main challenge in writing the book was sharing his perspectives as a professional historian and person of faith in a way that would “get readers to question their attitude towards these weird events.” He explained that the goal wasn’t to convince readers that these events did or did not happen, but rather more so that they aren’t necessarily impossible. For Eire, that question begins with the testimonies of these events that have been passed on.

“What criteria do you use to judge whether the testimony is credible or not? Same as you would in a court of law. Well, these phenomena that I studied all took place during a time when new methods and criteria were being established for veracity of verical cuts and wonders and anomalous events. The Catholical church became much more scientific about the handling of evidence. Those testimonies are different in kind from the testimonies from the 16th and 17th century because of the criteria that should be applied to the judging of testimonies; they’re more credible,” Eire said.

While it might seem like Eire’s work would struggle to find supporters or even willing skeptics, he has started receiving emails from people interested in paranormal and psychic phenomena. After all, how long could one really resist stories of flying monks and bi-locating saints? One of the most interesting interactions was from someone who had participated in “remote viewing” during the Cold War – an activity where someone in one room can reportedly see things in remote locations under special training. As crazy as it may sound, this practice was used by both the CIA and the KGB during the Cold War. Perhaps even crazier: it worked, and the person reaching out claimed that he had bi-located during one of the remote viewing sessions.

In the email, the remote viewer shared that during his bi-location experiences, he would leave where he was and go to the other place. He claimed he could talk to other people there and they would talk back. While the CIA didn’t seem to enjoy these experiences according to his accounts, he said it happened quite regularly.

“So I’m entering a whole new area. Talk about weird. This puts me on the same end of the spectrum of paranormal activity as UFOs, near-death experiences, clairvoyance, all of these things that are quite often exploited for entertainment value. It’s an unknown territory for me,” Eire said.

I asked Eire if he thought it was unhelpful for people to be able to describe exactly what was going on, and he shared that sometimes he did, that he was afraid of crossing certain lines. Part of it was a fear of losing his credibility, of becoming “known as a historian who chases after UFOs.” But another part was due to his loyalty to remaining skeptical to these phenomena outside of his experience.

Eire’s skepticism, though, isn’t one of disbelief, but rather comes from encountering evidence and testimonies that he has “no place to put in [his] mental structure.” He did share that he felt more comfortable with the topic of flying monks and bi-locating saints since he had been studying Christian mysticism and the 16th/17th century time period for the whole of his professional life.

“There’s a long tradition of, I would say ‘coping with’ this type of weird stuff in the Catholic tradition. I find it very interesting that at the beginning of the Protestant Reformation, the major leaders were convinced that if these things happened, they didn’t have a divine art. I think Protestants no longer cringe when they hear about these things because they understand that the challenged being posed is like a domino effect; if you knock this one down, everything falls down. Maybe it’s good to think that there are ways in which spiritual realities can manifest themselves in such strange ways,” Eire said.

As stated before, Eire’s quest when writing isn’t to get his readers to believe, but to get them to ask. You might wonder, especially when encountering phenomena such as flying monks, “How do we ask questions?” Eire begs his readers to simply keep asking questions, over and over again. You might get answers that make sense to you, but you’ll get even better questions when you get answers that don’t make sense.

At the end of the interview, I felt a little overwhelmed by all of the skepticism I had entered into. I mean, here I was talking to a historian, someone who I’ve been taught is supposed to be one of the people who “knows”, telling me he couldn’t and wouldn’t claim to.

“How would you define the difference between saying ‘I know’ versus ‘I believe’?” I asked.

Eire paused, smiled, and let out a small “Ooo” before answering.

“I know is when you’ve had a personal experience of something that’s otherworldly. I know. I believe. What’s the line there? Can I explain the Trinity? Can I imagine what it’s like for Jesus to be fully human and at the same time fully divine? There are things that the religion itself has ascertained to be true, but all those deepest truths about the Christian faith are highly paradoxical and incomprehensible. As a historian and as a thinker, that’s what makes me believe. I believe because it is absurd. If I understood it, then it wouldn’t be transcendent. There’s no getting around the weirdness of it all.”

I know. I believe. I’m skeptical. After emptying my list of questions into my interview with Eire, I left feeling ready to ask a million more. It was a wonderful experience having Eire with us at Eastern, and perhaps his honest questioning about history and Christianity can teach us something about what it means to be a Christian who asks questions and believes.